(Redirected from Online learning in Higher Education) Online learning involves courses offered by postsecondary institutions that are 199% virtual, excluding massively open online courses (MOOCs). Earn a degree from a leading university Fit learning around your life with an online degree from a leading university. From undergraduate to postgraduate degrees, find the right.

Online learning involves courses offered by postsecondary institutions that are 199% virtual, excluding massively open online courses (MOOCs). Online learning, or virtual classes offered over the internet, is contrasted with traditional courses taken in a brick-and-mortar school building. It is the newest development in distance education that began in the mid-1990s with the spread of the internet and the World Wide Web. Learner experience is typically asynchronous, but may also incorporate synchronous elements. The vast majority of institutions utilize a Learning Management System for the administration of online courses. As theories of distance education evolve, digital technologies to support learning and pedagogy continue to transform as well.

History[edit]

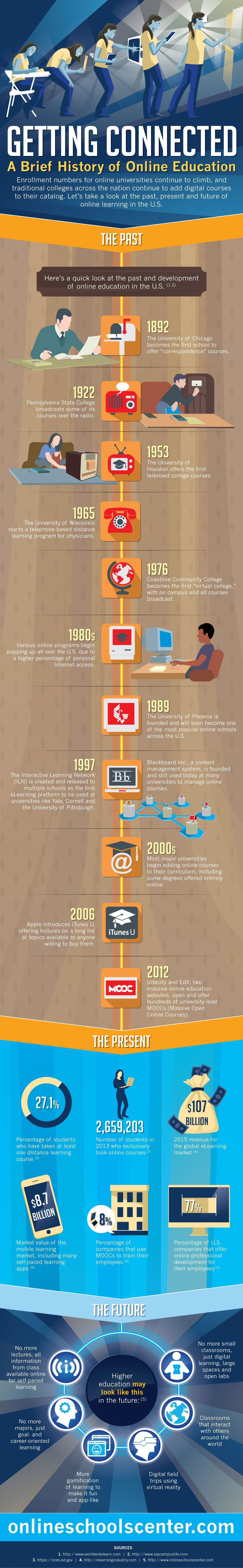

The first correspondence courses began in the 1800s using parcel post to reach students who couldn't be on a university campus.[1] By the early 1900s, communication technologies improved and distance education took to the radio waves. In 1919 professors at the University of Wisconsin began an amateur radio station, becoming the first licensed radio station dedicated to educational broadcasting.[1] Soon after, access to higher education was again expanded through the invention of the television; giving birth to what was known as the telecourse. The University of Iowa began to experiment with television for educational purposes in the 1930s. It was not until the 1950s, when the FCC began to reserve television frequencies for educational purposes, that telecourses caught the attention of the public. The value of television for education was furthered by the establishment of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) in 1967. The CPB mission was 'to encourage the growth and development of public radio and television broadcasting, including the use of such media for instructional, educational, and cultural purposes' (as cited in,[1] p. 27).

When looking at online MBA programs in the U.S., international students may want to consider student body diversity and career resources. Degree-seeking students learning online can be eligible. Online education is not a new phenomenon. It has its roots in distance education and the emergence of digital technologies that facilitate the efficient and reliable delivery of lectures, virtual classroom sessions, and other instructional materials and activities via the Internet.

Online learning emerged in 1982 when the Western Behavioral Sciences Institute in La Jolla, California opened its School of Management and Strategic Studies. The School employed computer conferencing to deliver a distance education program to business executives.[2] In 1989 the University of Phoenix began offering education programs through the internet. In 1993 with the debut of the first Internet web browser, created by the University of Illinois, online learning began to flourish.[3] In 1998, the first fully online programs were founded: New York University Online, Western Governor's University, the California Virtual University[3] and Trident University International.[4][5]

The Educational Technology Leadership Program, through the Graduate School of Education and Human Development at The George Washington University, offered a Masters degree beginning in 1992. The program, developed by Dr. William Lynch, originally delivered course content in association with Jones Intercable's Mind Extension University (ME/U). Classes were broadcast via satellite late at night, and student communicated through a Bulletin Board system. Their first cohort graduated in May, 1994. By early 1996, Bill Robie transitioned the ETL Program to the Internet where the graduate degree program was offered completely online. He assembled a set of web-based tools and HTML pages that allowed asynchronous communication among students and faculty, the delivery of lectures, drop boxes for assignments, and other features that have since become the core toolkit for course management systems.[6][7]

In 2000 only 8% of students were enrolled in an online course, but by 2008 enrollment had increased to 20%.[8] The expansion of online education has not slowed either; by the fall of 2013 nearly 30% of all postsecondary students were enrolled in some kind of distance education course.[9] Although the data on online course and program completion are complex,[10] researchers have noted high rates of attrition (ranging from 20%-50%) among students enrolled in online courses compared to those who take traditional face-to-face courses.[11]

In 2020, the global coronavirus pandemic prompted many universities to hastily transition to online learning in lieu of holding classes in person.[12][13][14][15]

Online operators (methods of delivery)[edit]

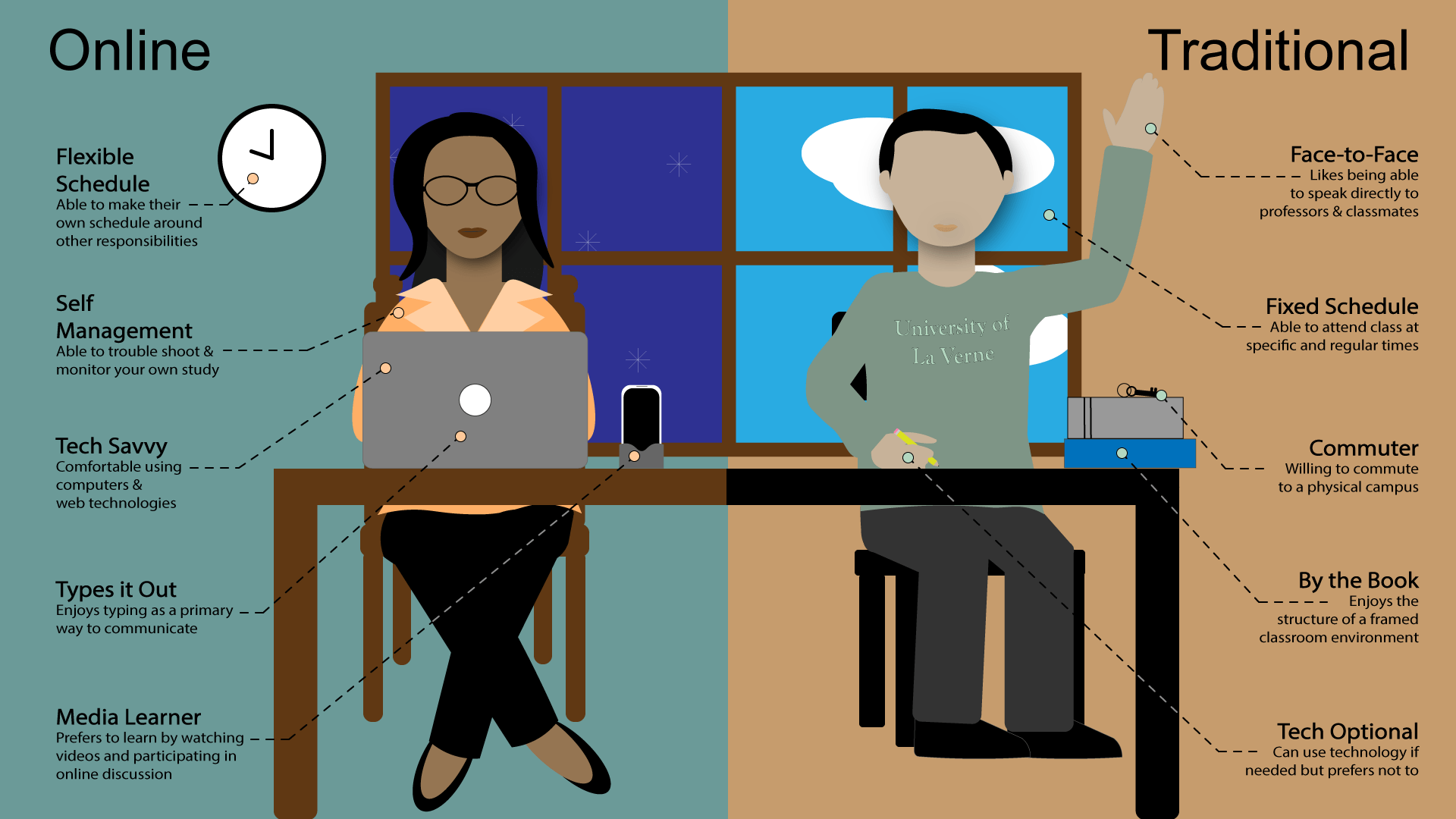

Given the improvements in delivery methods, online learning environments provide a greater degree of flexibility than traditional classroom settings.[16][17] Online platforms can also offer more diverse representations of student populations as learners prepare for working in the twenty-first century.[18] The diversity comes from interacting with students outside of one's geographical location, possibly offering a variety of perspectives on course content.[18] The courses themselves can also incorporate a wider range of available learning technologies.[19] Courses offered completely online are primarily delivered in an asynchronous learning or synchronous learning format.

Asynchronous learning environments are described as online spaces where work is supported through the use of digital platforms in such a way that participants are not required to be online at the same time.[20][21] Threaded discussions, e-mail, and telephone calls are options of asynchronous delivery.[22] This gives meaning to the anytime-anywhere appeal of online learning.[23] A benefit of asynchronous learning is the learner having more time to generate content-related responses to the instructor and peer postings; they have time to find facts to back their written statements.[20] The additional time provides an opportunity to increase the learner's ability to process information.[20] The spelling and grammar within postings of an asynchronous environment are like that found in formal academic writing.[24] On the other hand, one of the main limitations of this delivery method is the greater potential for a learner to feel removed from the learning environment. Asynchronous learning is viewed as less social in nature and can cause the learner to feel isolated.[20] Providing the student a feeling of belonging to the university or institution will assist with feelings of isolation; this can be done through ensuring links to university support systems and the library are accessible and operable.[22]

Synchronous learning environments most closely resemble face-to-face learning.[16][21] Synchronous learning takes place through digital platforms where the learners are utilizing the online media at the same time. When compared to asynchronous learning, synchronous online environments provide a greater sense of feeling supported, as the exchange of text or voice is immediate and feels more like a conversation.[16] If platforms such as web conferencing or video chat are used, learners are able to hear the tone of voice used by others which may allow for greater understanding of content.[18] As in a traditional classroom environment, online learners may feel a need to keep the conversation going, so there is a potential for focusing on the quantity of responses over the quality of content within the response.[20] However the synchronous environment, with real-time responses, can allow for students or instructors to provide clarity to what was said, or alleviate any possible misconceptions.[16]

Along these lines and applying the two dimensions of 'time distance' and 'number of participants', one can classify online distance courses into four distinct groups:[25]

- MOOCs (massive open online courses): unlimited in the number of participants, enabling them to learn asynchronously at their own pace.

- SMOCs (synchronous massive online courses): unlimited in the number of participants, in which students participate synchronously and in real-time.

- SPOCs (small private online courses) number of students is limited, learning takes place in an asynchronous manner.

- SSOCs (synchronous small online courses) number of students is limited,require participants to follow the lessons in real time.

Learning management systems[edit]

Most online learning occurs through a college's or university's learning management system (LMS). A LMS is a software application for maintaining, delivering, and tracking educational resources. According to the Educause Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR) use of a LMS is nearly ubiquitous as 99% of colleges and universities report having one in place.[26] Among faculty, 87% report using a LMS and find them useful for 'enhancing teaching (74%) and student learning (71%)' [26](p. 10). Similarly, 83% of students use an LMS for their learning, with the majority (56%) using them in most or all courses.

Most institutions utilize LMSs by external vendors (77%), Blackboard currently dominates the LMS environment with an adoption rate of 31.9%, followed by Moodle at 19.1%, and Canvas at 15.3%.[27] However, in the last year Canvas, by Instructure, has gained an increasing amount of the market share (see graphic).

Reflecting these changes the ECAR reported that 15% of institutions are in the process of updating and/or replacing their LMS; the main reasons cited were the need to 'upgrade functions (71%), replace legacy systems (44%), and reduce costs (18%)' [26](p. 6).

ECAR's survey of institutions found that generally, both faculty and students are satisfied with the LMS; with three-quarters satisfied with the LMS for posting content (faculty) and accessing content (students).[26] In contrast, the lowest levels of satisfaction with the LMS reported by faculty were with features that allow for 'meaningful' interaction between students and their instructor, students and other students, and for study groups or collaborating on projects (p. 12). Similarly, just under half of the students surveyed reported satisfaction of the LMS for 'engaging in meaningful interactions with students' (p. 12).

While LMSs are largely being used as a repository for course materials (e.g. syllabus, learning content, etc.) and platforms for the assessment of learning, recent developments are making them more customizable through LTI standards.[26] According to a report by the Educause Learning Initiative the Next Generation Digital Learning Environment will be more responsive to students' needs creating a more customizable experience. The functional characteristics of the next generation of digital learning environments include: 'interoperability and integration; personalization; analytics, advising, and learning assessments; collaboration; and, accessibility and universal design'[28] (p. 4)

Theory[edit]

The well-known educational theorist John Dewey argued that learning occurs in collaboration with knowledgeable others.[29] Similarly, psychologist Jean Piaget noted that in order for learning to occur, the content must be meaningful to the student. Piaget's constructivist theory of learning highlighted the importance of engaged learning where meaningful discussions were held between peers.[30] The sociologist Lev Vygotsky also emphasized the importance of social interaction in learning.[31] Traditionally, in formal education this interaction occurs largely between the student and the teacher, but as students and teachers become distanced from each other in the virtual classroom, creative strategies for instruction continue to be developed.[32] While early approaches to online learning were merely an extension of independently-driven correspondence courses, today's approach to online learning focuses on engagement and active learning.

Theories of distance education are relatively new to the scene. These theories can be placed into four main categories: 1) theories of independent study (e.g. Charles Wedemeyer, Michael Moore); 2) theories of the industrialization of teaching (e.g. Otto Peters); 3) theories of interaction and communication (e.g. Borje Holmberg); and 4) a synthesis of existing theories of communication and diffusion and philosophies of education (e.g. Hilary Perraton).[33] However, the equivalency theory of distance education posits that all students should have learning experiences of equal value and that it is the responsibility of the instructional designer to create learning experiences for the distance learner that will be successful in meeting the course objectives.[33] As online education has become the dominant form of distance education, new theories are emerging that combine elements of constructivism and technology. Siemens' Connectivism 'is the integration of principles explored by chaos, network, and complexity and self-organization theories'.(p. 5[34]) Connectivism places knowledge in 'diversity of opinions' (p. 5) and that learning is aided through creating and nurturing connections of 'fields, ideas, and concepts'. (p. 5[34])

Pedagogy[edit]

Transformative learning or Transformative pedagogy 'encourages students to critically examine their assumptions, grapple with social issues, and engage in social action' ( p. 219[35]). Five suggestions for preparing the online environment for transformative pedagogy are: '(a) create a safe and inviting environment; (b) encourage students to think about their experiences, beliefs, and biases; (c) use teaching strategies that promote student engagement and participation; (d) pose real-world problems that address societal inequalities; and (e) help students implement action-oriented solutions' (p. 220[35]). There are four fundamental characteristics that may assist with the success of online instruction: (1) the learner should be actively engaged throughout the course; (2) group participation can assist with meeting course objectives; (3) frequent student-student and student-teacher interaction can alleviate the feelings of isolation; and (4) the course content should relate to the real world to enhance meaning for participants.[36] However, a student's attitude towards using technology and computers is led by the teacher's ability to impact a student's values and beliefs.[citation needed]

Participation and interaction between participants and instructors involves significant and continuous preparation.[21] Online educators are often members of a larger team consisting of instructional and graphic designers and information technology specialists; being open to becoming a member of the team will assist in a smooth transition to online teaching.[21] There is a lack of support and training provided for teachers, hence instructors require training and support first before they can combine technology, content, and pedagogy to design courses.[37] Expectations of learners to be self-motivated, able to manage their time effectively, contribute to course discussions and have a willingness to teach others is not unlike what is expected in a traditional classroom. The instructor's role is to encourage learners to evaluate and analyze information, then connect the information to course content which may assist in learner success.[21] With the potential for learners to feel disconnected from peers within the course, the instructor will need to work to create spaces and encounters which promote socialization. A few recommendations are to create a 'student lounge' as an informal space for socialization not related to coursework.[21] Also, incorporating team projects can help alleviate feelings of isolation.[21] Video and audio components enhance connection and communication with peers, as this supports learners to expand on their responses and engage in discussions.[37] Online instructors should be cognizant of where participants are physically located; when members of the course span two or more time zones, the timing of the course can become problematic.[22] Initial preparation of an online course is often more time-consuming than preparation for the classroom. The material must be prepared and posted, in its entirety, prior to the course start.[22] In addition to preparation, faculty experienced in online instruction spend about 30% more time on courses conducted online.[22] The mentoring of novice online educators from those with experience can assist with the transition from classroom to the virtual environment.[22]

Online credentials[edit]

Online credentials for learning are digital credentials that are offered in place of traditional paper credentials for a skill or educational achievement. Directly linked to the accelerated development of internet communication technologies, the development of digital badges, electronic passports and massive open online courses (MOOCs) have a very direct bearing on our understanding of learning, recognition and levels as they pose a direct challenge to the status quo. It is useful to distinguish between three forms of online credentials: Test-based credentials, online badges, and online certificates.[38]

Sources[edit]

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0 License statement/permission on Wikimedia Commons. Text taken from Level-setting and recognition of learning outcomes: The use of level descriptors in the twenty-first century, 129-131, Keevey, James, UNESCO. UNESCO.

References[edit]

- ^ abcKentnor, H. (2015). 'Distance education and the evolution of online learning in the United States'. Curriculum and Teaching Dialogue. 17: 21–34.

- ^See Rowan, Roy (1983). Executive Ed. at Computer U. Fortune, March 7, 1983; Feenberg, Andrew (1993). 'Building a Global Network: The WBSI Experience,' in L. Harasim, ed., Global Networks: Computerizing the International Community, MIT Press, pp. 185-197.

- ^ abMiller, Gary; Benke, Meg; Chaloux, Bruce; Ragan, Lawrence C.; Schroeder, Raymond; Smutz, Wayne; Swan, Karen (204). Leading the e-learning transformation of higher education. Sterling, Virginia: Stylus. ISBN978-1-57922-796-8.

- ^'Company Overview of Trident University International'. www.bloomberg.com.

- ^'Trident University International LLC Overview'. www.bbb.org.

- ^https://www.educause.edu/apps/er/review/reviewArticles/29626.html

- ^https://web.archive.org/web/19970301032852/http://www.gwu.edu/~etl/

- ^Radford, A.W. (2011). 'Learning at a Distance: Undergraduate Enrollment in Distance Education Courses and Degree Programs'. nces.ed.gov.

- ^National Center for Education Statistics (2016). 'Digest of education statistics, 2014'. nces.ed.gov. U.S. Department of Education.

- ^Haynie, D. (January 30, 2015). 'Experts debate graduation rates for online students'. U. S. News & World Report.

- ^Jazzar, M. (December 7, 2012). 'Online student retention strategies: A baker's dozen of recommendations'. Faculty Focus.

- ^https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/will-coronavirus-make-online-education-go-viral

- ^https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/18/opinion/college-education-coronavirus.html

- ^https://www.npr.org/2020/03/19/817885991/panic-gogy-teaching-online-classes-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic

- ^Aristovnik A, Keržič D, Ravšelj D, Tomaževič N, Umek L (October 2020). 'Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Life of Higher Education Students: A Global Perspective'. Sustainability. 12 (20): 8438. doi:10.3390/su12208438.

- ^ abcdGiesbers, B.; Rienties, B.; Tempelaar, D.; Gijselaers, W. (2014-02-01). 'A dynamic analysis of the interplay between asynchronous and synchronous communication in online learning: The impact of motivation'. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. 30 (1): 30–50. doi:10.1111/jcal.12020. ISSN1365-2729.

- ^Online learning is more flexibility than traditional university college settings. March 28, 2020

- ^ abcStewart, Anissa R.; Harlow, Danielle B. & DeBacco, Kim (2011). 'Students' experiences of synchronous learning in distributed environments'. Distance Education. 32 (3): 357–381.

- ^Newlin, Timothy (14 January 2021). 'How We Navigated a Hybrid Remote Learning Environment Using Wolfram Technology'. Wolfram Blog.

- ^ abcdeHrastinski, Stefan (2008). 'Asynchronous and synchronous e-learning'. Educause Quarterly. 4: 51–55.

- ^ abcdefgHanna, Donald E.; Glowacki-Dudka, Michelle & Conceicao-Runlee, Simone (2000). 147 practical tips for teaching online groups. Madison, Wisconsin: Atwood Publishing.

- ^ abcdefLieblein, Edward (2000). 'Critical factors for successful delivery of online programs'. Internet and Higher Education. 3: 161–174.

- ^Johnson, Henry M (2007). 'Dialogue and the construction of knowledge in e-learning: Exploring students' perceptions of their learning while using Blackboard's asynchronous discussion board'(PDF). European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning. 10 (1). Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^Ho, Chia-Huan; Swan, Karen (2007). 'Evaluating online conversation in an asynchronous environment: An application of Grice's Cooperative'. Internet and Higher Education. 10 (1): 3–14.

- ^'Andreas Kaplan (2017) Academia Goes Social Media, MOOC, SPOC, SMOC, and SSOC: The digital transformation of Higher Education Institutions and Universities, in Bikramjit Rishi and Subir Bandyopadhyay (eds.), Contemporary Issues in Social Media Marketing, Routledge'.

- ^ abcdeDahlstrom, Eden; Brooks, D. Christopher; Bichsel, Jacqueline (September 17, 2014). 'The current ecosystem of Learning Management Systems in Higher Education: Student, faculty, and IT perspectives'. Educause.

- ^'LMS data – Spring 2016 updates'. edutechnica. March 20, 2016. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ^Brown, M.; Dehoney, J.; Millichap, N. (April 27, 2015). 'The next generation digital learning environment: A report on research'. Educause.

- ^Dewey, John (1997) [1916]. Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: The Free Press.

- ^Piaget, Jean (2006) [1969]. The mechanisms of perception. Abingdon, OX: Routledge.

- ^Vygotsky, L. S. (1997). Rieber, R. W. (ed.). The genesis of higher mental functions. The collected works of L.S. Vygotsky. New York, NY: Springer. pp. 97–119.

- ^Conrad, R.-M.; Donaldson, J. A. (2004). Engaging the online learner. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- ^ abSimonson, M.; Smaldino, S.; Albright, M.; Zvacek, S. (203). Teaching and learning at a distance (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

- ^ abSiemens, George (2005). 'Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age'. International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning. 2 (1).

- ^ abMyers, Steven A (2008). 'Using transformative pedagogy when teaching online'. College Teaching. 56 (4): 219–224.

- ^McFarlane, Donovan A (2011). 'Are there differences in the organizational structure and pedagogical approach of virtual and brick-and-mortar schools?'. The Journal of Educators Online. 8 (1): 1–43.

- ^ abKebritchi, M.; Lipschuetz, A. & Santiague, L. (2017). 'Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher education: A literature review'. Journal of Educational Technology Systems. 46 (1): 4–29. doi:10.1177/0047239516661713.

- ^Keevy, James; Chakroun, Borhene (2015). Level-setting and recognition of learning outcomes: The use of level descriptors in the twenty-first century(PDF). Paris, UNESCO. pp. 129–131. ISBN978-92-3-100138-3.

Online learning may not appeal to everyone; however, the sheer number of online learning sites suggests that there is at least a strong interest in convenient, portable learning options — many of which are study-at-your-own-pace. For your reference, we've selected 50 top learning sites and loosely collected them into the categories you'll find below. While this is not a rankings list by any means, (for that you should consult our ranking of the best online colleges) by using a variety of criteria, we've filtered in some of the most popular sites in each category.

Featured Online Schools

Many of these sites offer free lessons; some require payment or offer verified certification for a nominal fee. Some sites offer very general non-academic lessons, others provided actual college / university curriculum course material. Whatever you are looking to learn, check out the list below before trying to wade through pages of search engine listings.

Art and Music

- Dave Conservatoire — Dave Conservatoire is an entirely free online music school offering a self-proclaimed 'world-class music education for everyone,' and providing video lessons and practice tests.

- Drawspace — If you want to learn to draw or improve your technique, Drawspace has free and paid self-study as well as interactive, instructor-led lessons.

- Justin Guitar — The Justin Guitar site boasts over 800 free guitar lessons which cover transcribing, scales, arpeggios, ear training, chords, recording tech and guitar gear, and also offers a variety of premium paid mobile apps and content (books/ ebooks, DVDs, downloads).

Math, Data Science and Engineering

- Codecademy — Codecademy offers data science and software programming (mostly Web-related) courses for various ages groups, with an in-browser coding console for some offerings.

- Stanford Engineering Everywhere — SEE/ Stanford Engineering Everywhere houses engineering (software and otherwise) classes that are free to students and educators, with materials that include course syllabi, lecture videos, homework, exams and more.

- Big Data University — Big Data University covers Big Data analysis and data science via free and paid courses developed by teachers and professionals.

- Better Explained — BetterExplained offers a big-picture-first approach to learning mathematics — often with visual explanations — whether for high school algebra or college-level calculus, statistics and other related topics.

Design, Web Design/ Development

- HOW Design University — How Design University (How U) offers free and paid online lessons on graphic and interactive design, and has opportunities for those who would like to teach.

- HTML Dog — HTML Dog is specifically focused on Web development tutorials for HTML, CSS and JavaScript coding skills.

- Skillcrush — Skillcrush offers professional web design and development courses aimed at one who is interested in the field, regardless of their background — with short, easy-to-consume modules and a 3-month Career Blueprints to help students focus on their career priorities.

- Hack Design — Hack Design, with the help of several dozen designers around the world, has put together a lesson plan of 50 units (each with one or more articles and/or videos) on design for Web, mobile apps and more by curating multiple valuable sources (blogs, books, games, videos, and tutorials) — all free of charge.

Online learning involves courses offered by postsecondary institutions that are 199% virtual, excluding massively open online courses (MOOCs). Online learning, or virtual classes offered over the internet, is contrasted with traditional courses taken in a brick-and-mortar school building. It is the newest development in distance education that began in the mid-1990s with the spread of the internet and the World Wide Web. Learner experience is typically asynchronous, but may also incorporate synchronous elements. The vast majority of institutions utilize a Learning Management System for the administration of online courses. As theories of distance education evolve, digital technologies to support learning and pedagogy continue to transform as well.

History[edit]

The first correspondence courses began in the 1800s using parcel post to reach students who couldn't be on a university campus.[1] By the early 1900s, communication technologies improved and distance education took to the radio waves. In 1919 professors at the University of Wisconsin began an amateur radio station, becoming the first licensed radio station dedicated to educational broadcasting.[1] Soon after, access to higher education was again expanded through the invention of the television; giving birth to what was known as the telecourse. The University of Iowa began to experiment with television for educational purposes in the 1930s. It was not until the 1950s, when the FCC began to reserve television frequencies for educational purposes, that telecourses caught the attention of the public. The value of television for education was furthered by the establishment of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) in 1967. The CPB mission was 'to encourage the growth and development of public radio and television broadcasting, including the use of such media for instructional, educational, and cultural purposes' (as cited in,[1] p. 27).

When looking at online MBA programs in the U.S., international students may want to consider student body diversity and career resources. Degree-seeking students learning online can be eligible. Online education is not a new phenomenon. It has its roots in distance education and the emergence of digital technologies that facilitate the efficient and reliable delivery of lectures, virtual classroom sessions, and other instructional materials and activities via the Internet.

Online learning emerged in 1982 when the Western Behavioral Sciences Institute in La Jolla, California opened its School of Management and Strategic Studies. The School employed computer conferencing to deliver a distance education program to business executives.[2] In 1989 the University of Phoenix began offering education programs through the internet. In 1993 with the debut of the first Internet web browser, created by the University of Illinois, online learning began to flourish.[3] In 1998, the first fully online programs were founded: New York University Online, Western Governor's University, the California Virtual University[3] and Trident University International.[4][5]

The Educational Technology Leadership Program, through the Graduate School of Education and Human Development at The George Washington University, offered a Masters degree beginning in 1992. The program, developed by Dr. William Lynch, originally delivered course content in association with Jones Intercable's Mind Extension University (ME/U). Classes were broadcast via satellite late at night, and student communicated through a Bulletin Board system. Their first cohort graduated in May, 1994. By early 1996, Bill Robie transitioned the ETL Program to the Internet where the graduate degree program was offered completely online. He assembled a set of web-based tools and HTML pages that allowed asynchronous communication among students and faculty, the delivery of lectures, drop boxes for assignments, and other features that have since become the core toolkit for course management systems.[6][7]

In 2000 only 8% of students were enrolled in an online course, but by 2008 enrollment had increased to 20%.[8] The expansion of online education has not slowed either; by the fall of 2013 nearly 30% of all postsecondary students were enrolled in some kind of distance education course.[9] Although the data on online course and program completion are complex,[10] researchers have noted high rates of attrition (ranging from 20%-50%) among students enrolled in online courses compared to those who take traditional face-to-face courses.[11]

In 2020, the global coronavirus pandemic prompted many universities to hastily transition to online learning in lieu of holding classes in person.[12][13][14][15]

Online operators (methods of delivery)[edit]

Given the improvements in delivery methods, online learning environments provide a greater degree of flexibility than traditional classroom settings.[16][17] Online platforms can also offer more diverse representations of student populations as learners prepare for working in the twenty-first century.[18] The diversity comes from interacting with students outside of one's geographical location, possibly offering a variety of perspectives on course content.[18] The courses themselves can also incorporate a wider range of available learning technologies.[19] Courses offered completely online are primarily delivered in an asynchronous learning or synchronous learning format.

Asynchronous learning environments are described as online spaces where work is supported through the use of digital platforms in such a way that participants are not required to be online at the same time.[20][21] Threaded discussions, e-mail, and telephone calls are options of asynchronous delivery.[22] This gives meaning to the anytime-anywhere appeal of online learning.[23] A benefit of asynchronous learning is the learner having more time to generate content-related responses to the instructor and peer postings; they have time to find facts to back their written statements.[20] The additional time provides an opportunity to increase the learner's ability to process information.[20] The spelling and grammar within postings of an asynchronous environment are like that found in formal academic writing.[24] On the other hand, one of the main limitations of this delivery method is the greater potential for a learner to feel removed from the learning environment. Asynchronous learning is viewed as less social in nature and can cause the learner to feel isolated.[20] Providing the student a feeling of belonging to the university or institution will assist with feelings of isolation; this can be done through ensuring links to university support systems and the library are accessible and operable.[22]

Synchronous learning environments most closely resemble face-to-face learning.[16][21] Synchronous learning takes place through digital platforms where the learners are utilizing the online media at the same time. When compared to asynchronous learning, synchronous online environments provide a greater sense of feeling supported, as the exchange of text or voice is immediate and feels more like a conversation.[16] If platforms such as web conferencing or video chat are used, learners are able to hear the tone of voice used by others which may allow for greater understanding of content.[18] As in a traditional classroom environment, online learners may feel a need to keep the conversation going, so there is a potential for focusing on the quantity of responses over the quality of content within the response.[20] However the synchronous environment, with real-time responses, can allow for students or instructors to provide clarity to what was said, or alleviate any possible misconceptions.[16]

Along these lines and applying the two dimensions of 'time distance' and 'number of participants', one can classify online distance courses into four distinct groups:[25]

- MOOCs (massive open online courses): unlimited in the number of participants, enabling them to learn asynchronously at their own pace.

- SMOCs (synchronous massive online courses): unlimited in the number of participants, in which students participate synchronously and in real-time.

- SPOCs (small private online courses) number of students is limited, learning takes place in an asynchronous manner.

- SSOCs (synchronous small online courses) number of students is limited,require participants to follow the lessons in real time.

Learning management systems[edit]

Most online learning occurs through a college's or university's learning management system (LMS). A LMS is a software application for maintaining, delivering, and tracking educational resources. According to the Educause Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR) use of a LMS is nearly ubiquitous as 99% of colleges and universities report having one in place.[26] Among faculty, 87% report using a LMS and find them useful for 'enhancing teaching (74%) and student learning (71%)' [26](p. 10). Similarly, 83% of students use an LMS for their learning, with the majority (56%) using them in most or all courses.

Most institutions utilize LMSs by external vendors (77%), Blackboard currently dominates the LMS environment with an adoption rate of 31.9%, followed by Moodle at 19.1%, and Canvas at 15.3%.[27] However, in the last year Canvas, by Instructure, has gained an increasing amount of the market share (see graphic).

Reflecting these changes the ECAR reported that 15% of institutions are in the process of updating and/or replacing their LMS; the main reasons cited were the need to 'upgrade functions (71%), replace legacy systems (44%), and reduce costs (18%)' [26](p. 6).

ECAR's survey of institutions found that generally, both faculty and students are satisfied with the LMS; with three-quarters satisfied with the LMS for posting content (faculty) and accessing content (students).[26] In contrast, the lowest levels of satisfaction with the LMS reported by faculty were with features that allow for 'meaningful' interaction between students and their instructor, students and other students, and for study groups or collaborating on projects (p. 12). Similarly, just under half of the students surveyed reported satisfaction of the LMS for 'engaging in meaningful interactions with students' (p. 12).

While LMSs are largely being used as a repository for course materials (e.g. syllabus, learning content, etc.) and platforms for the assessment of learning, recent developments are making them more customizable through LTI standards.[26] According to a report by the Educause Learning Initiative the Next Generation Digital Learning Environment will be more responsive to students' needs creating a more customizable experience. The functional characteristics of the next generation of digital learning environments include: 'interoperability and integration; personalization; analytics, advising, and learning assessments; collaboration; and, accessibility and universal design'[28] (p. 4)

Theory[edit]

The well-known educational theorist John Dewey argued that learning occurs in collaboration with knowledgeable others.[29] Similarly, psychologist Jean Piaget noted that in order for learning to occur, the content must be meaningful to the student. Piaget's constructivist theory of learning highlighted the importance of engaged learning where meaningful discussions were held between peers.[30] The sociologist Lev Vygotsky also emphasized the importance of social interaction in learning.[31] Traditionally, in formal education this interaction occurs largely between the student and the teacher, but as students and teachers become distanced from each other in the virtual classroom, creative strategies for instruction continue to be developed.[32] While early approaches to online learning were merely an extension of independently-driven correspondence courses, today's approach to online learning focuses on engagement and active learning.

Theories of distance education are relatively new to the scene. These theories can be placed into four main categories: 1) theories of independent study (e.g. Charles Wedemeyer, Michael Moore); 2) theories of the industrialization of teaching (e.g. Otto Peters); 3) theories of interaction and communication (e.g. Borje Holmberg); and 4) a synthesis of existing theories of communication and diffusion and philosophies of education (e.g. Hilary Perraton).[33] However, the equivalency theory of distance education posits that all students should have learning experiences of equal value and that it is the responsibility of the instructional designer to create learning experiences for the distance learner that will be successful in meeting the course objectives.[33] As online education has become the dominant form of distance education, new theories are emerging that combine elements of constructivism and technology. Siemens' Connectivism 'is the integration of principles explored by chaos, network, and complexity and self-organization theories'.(p. 5[34]) Connectivism places knowledge in 'diversity of opinions' (p. 5) and that learning is aided through creating and nurturing connections of 'fields, ideas, and concepts'. (p. 5[34])

Pedagogy[edit]

Transformative learning or Transformative pedagogy 'encourages students to critically examine their assumptions, grapple with social issues, and engage in social action' ( p. 219[35]). Five suggestions for preparing the online environment for transformative pedagogy are: '(a) create a safe and inviting environment; (b) encourage students to think about their experiences, beliefs, and biases; (c) use teaching strategies that promote student engagement and participation; (d) pose real-world problems that address societal inequalities; and (e) help students implement action-oriented solutions' (p. 220[35]). There are four fundamental characteristics that may assist with the success of online instruction: (1) the learner should be actively engaged throughout the course; (2) group participation can assist with meeting course objectives; (3) frequent student-student and student-teacher interaction can alleviate the feelings of isolation; and (4) the course content should relate to the real world to enhance meaning for participants.[36] However, a student's attitude towards using technology and computers is led by the teacher's ability to impact a student's values and beliefs.[citation needed]

Participation and interaction between participants and instructors involves significant and continuous preparation.[21] Online educators are often members of a larger team consisting of instructional and graphic designers and information technology specialists; being open to becoming a member of the team will assist in a smooth transition to online teaching.[21] There is a lack of support and training provided for teachers, hence instructors require training and support first before they can combine technology, content, and pedagogy to design courses.[37] Expectations of learners to be self-motivated, able to manage their time effectively, contribute to course discussions and have a willingness to teach others is not unlike what is expected in a traditional classroom. The instructor's role is to encourage learners to evaluate and analyze information, then connect the information to course content which may assist in learner success.[21] With the potential for learners to feel disconnected from peers within the course, the instructor will need to work to create spaces and encounters which promote socialization. A few recommendations are to create a 'student lounge' as an informal space for socialization not related to coursework.[21] Also, incorporating team projects can help alleviate feelings of isolation.[21] Video and audio components enhance connection and communication with peers, as this supports learners to expand on their responses and engage in discussions.[37] Online instructors should be cognizant of where participants are physically located; when members of the course span two or more time zones, the timing of the course can become problematic.[22] Initial preparation of an online course is often more time-consuming than preparation for the classroom. The material must be prepared and posted, in its entirety, prior to the course start.[22] In addition to preparation, faculty experienced in online instruction spend about 30% more time on courses conducted online.[22] The mentoring of novice online educators from those with experience can assist with the transition from classroom to the virtual environment.[22]

Online credentials[edit]

Online credentials for learning are digital credentials that are offered in place of traditional paper credentials for a skill or educational achievement. Directly linked to the accelerated development of internet communication technologies, the development of digital badges, electronic passports and massive open online courses (MOOCs) have a very direct bearing on our understanding of learning, recognition and levels as they pose a direct challenge to the status quo. It is useful to distinguish between three forms of online credentials: Test-based credentials, online badges, and online certificates.[38]

Sources[edit]

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0 License statement/permission on Wikimedia Commons. Text taken from Level-setting and recognition of learning outcomes: The use of level descriptors in the twenty-first century, 129-131, Keevey, James, UNESCO. UNESCO.

References[edit]

- ^ abcKentnor, H. (2015). 'Distance education and the evolution of online learning in the United States'. Curriculum and Teaching Dialogue. 17: 21–34.

- ^See Rowan, Roy (1983). Executive Ed. at Computer U. Fortune, March 7, 1983; Feenberg, Andrew (1993). 'Building a Global Network: The WBSI Experience,' in L. Harasim, ed., Global Networks: Computerizing the International Community, MIT Press, pp. 185-197.

- ^ abMiller, Gary; Benke, Meg; Chaloux, Bruce; Ragan, Lawrence C.; Schroeder, Raymond; Smutz, Wayne; Swan, Karen (204). Leading the e-learning transformation of higher education. Sterling, Virginia: Stylus. ISBN978-1-57922-796-8.

- ^'Company Overview of Trident University International'. www.bloomberg.com.

- ^'Trident University International LLC Overview'. www.bbb.org.

- ^https://www.educause.edu/apps/er/review/reviewArticles/29626.html

- ^https://web.archive.org/web/19970301032852/http://www.gwu.edu/~etl/

- ^Radford, A.W. (2011). 'Learning at a Distance: Undergraduate Enrollment in Distance Education Courses and Degree Programs'. nces.ed.gov.

- ^National Center for Education Statistics (2016). 'Digest of education statistics, 2014'. nces.ed.gov. U.S. Department of Education.

- ^Haynie, D. (January 30, 2015). 'Experts debate graduation rates for online students'. U. S. News & World Report.

- ^Jazzar, M. (December 7, 2012). 'Online student retention strategies: A baker's dozen of recommendations'. Faculty Focus.

- ^https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/will-coronavirus-make-online-education-go-viral

- ^https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/18/opinion/college-education-coronavirus.html

- ^https://www.npr.org/2020/03/19/817885991/panic-gogy-teaching-online-classes-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic

- ^Aristovnik A, Keržič D, Ravšelj D, Tomaževič N, Umek L (October 2020). 'Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Life of Higher Education Students: A Global Perspective'. Sustainability. 12 (20): 8438. doi:10.3390/su12208438.

- ^ abcdGiesbers, B.; Rienties, B.; Tempelaar, D.; Gijselaers, W. (2014-02-01). 'A dynamic analysis of the interplay between asynchronous and synchronous communication in online learning: The impact of motivation'. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. 30 (1): 30–50. doi:10.1111/jcal.12020. ISSN1365-2729.

- ^Online learning is more flexibility than traditional university college settings. March 28, 2020

- ^ abcStewart, Anissa R.; Harlow, Danielle B. & DeBacco, Kim (2011). 'Students' experiences of synchronous learning in distributed environments'. Distance Education. 32 (3): 357–381.

- ^Newlin, Timothy (14 January 2021). 'How We Navigated a Hybrid Remote Learning Environment Using Wolfram Technology'. Wolfram Blog.

- ^ abcdeHrastinski, Stefan (2008). 'Asynchronous and synchronous e-learning'. Educause Quarterly. 4: 51–55.

- ^ abcdefgHanna, Donald E.; Glowacki-Dudka, Michelle & Conceicao-Runlee, Simone (2000). 147 practical tips for teaching online groups. Madison, Wisconsin: Atwood Publishing.

- ^ abcdefLieblein, Edward (2000). 'Critical factors for successful delivery of online programs'. Internet and Higher Education. 3: 161–174.

- ^Johnson, Henry M (2007). 'Dialogue and the construction of knowledge in e-learning: Exploring students' perceptions of their learning while using Blackboard's asynchronous discussion board'(PDF). European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning. 10 (1). Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^Ho, Chia-Huan; Swan, Karen (2007). 'Evaluating online conversation in an asynchronous environment: An application of Grice's Cooperative'. Internet and Higher Education. 10 (1): 3–14.

- ^'Andreas Kaplan (2017) Academia Goes Social Media, MOOC, SPOC, SMOC, and SSOC: The digital transformation of Higher Education Institutions and Universities, in Bikramjit Rishi and Subir Bandyopadhyay (eds.), Contemporary Issues in Social Media Marketing, Routledge'.

- ^ abcdeDahlstrom, Eden; Brooks, D. Christopher; Bichsel, Jacqueline (September 17, 2014). 'The current ecosystem of Learning Management Systems in Higher Education: Student, faculty, and IT perspectives'. Educause.

- ^'LMS data – Spring 2016 updates'. edutechnica. March 20, 2016. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ^Brown, M.; Dehoney, J.; Millichap, N. (April 27, 2015). 'The next generation digital learning environment: A report on research'. Educause.

- ^Dewey, John (1997) [1916]. Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: The Free Press.

- ^Piaget, Jean (2006) [1969]. The mechanisms of perception. Abingdon, OX: Routledge.

- ^Vygotsky, L. S. (1997). Rieber, R. W. (ed.). The genesis of higher mental functions. The collected works of L.S. Vygotsky. New York, NY: Springer. pp. 97–119.

- ^Conrad, R.-M.; Donaldson, J. A. (2004). Engaging the online learner. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- ^ abSimonson, M.; Smaldino, S.; Albright, M.; Zvacek, S. (203). Teaching and learning at a distance (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

- ^ abSiemens, George (2005). 'Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age'. International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning. 2 (1).

- ^ abMyers, Steven A (2008). 'Using transformative pedagogy when teaching online'. College Teaching. 56 (4): 219–224.

- ^McFarlane, Donovan A (2011). 'Are there differences in the organizational structure and pedagogical approach of virtual and brick-and-mortar schools?'. The Journal of Educators Online. 8 (1): 1–43.

- ^ abKebritchi, M.; Lipschuetz, A. & Santiague, L. (2017). 'Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher education: A literature review'. Journal of Educational Technology Systems. 46 (1): 4–29. doi:10.1177/0047239516661713.

- ^Keevy, James; Chakroun, Borhene (2015). Level-setting and recognition of learning outcomes: The use of level descriptors in the twenty-first century(PDF). Paris, UNESCO. pp. 129–131. ISBN978-92-3-100138-3.

Online learning may not appeal to everyone; however, the sheer number of online learning sites suggests that there is at least a strong interest in convenient, portable learning options — many of which are study-at-your-own-pace. For your reference, we've selected 50 top learning sites and loosely collected them into the categories you'll find below. While this is not a rankings list by any means, (for that you should consult our ranking of the best online colleges) by using a variety of criteria, we've filtered in some of the most popular sites in each category.

Featured Online Schools

Many of these sites offer free lessons; some require payment or offer verified certification for a nominal fee. Some sites offer very general non-academic lessons, others provided actual college / university curriculum course material. Whatever you are looking to learn, check out the list below before trying to wade through pages of search engine listings.

Art and Music

- Dave Conservatoire — Dave Conservatoire is an entirely free online music school offering a self-proclaimed 'world-class music education for everyone,' and providing video lessons and practice tests.

- Drawspace — If you want to learn to draw or improve your technique, Drawspace has free and paid self-study as well as interactive, instructor-led lessons.

- Justin Guitar — The Justin Guitar site boasts over 800 free guitar lessons which cover transcribing, scales, arpeggios, ear training, chords, recording tech and guitar gear, and also offers a variety of premium paid mobile apps and content (books/ ebooks, DVDs, downloads).

Math, Data Science and Engineering

- Codecademy — Codecademy offers data science and software programming (mostly Web-related) courses for various ages groups, with an in-browser coding console for some offerings.

- Stanford Engineering Everywhere — SEE/ Stanford Engineering Everywhere houses engineering (software and otherwise) classes that are free to students and educators, with materials that include course syllabi, lecture videos, homework, exams and more.

- Big Data University — Big Data University covers Big Data analysis and data science via free and paid courses developed by teachers and professionals.

- Better Explained — BetterExplained offers a big-picture-first approach to learning mathematics — often with visual explanations — whether for high school algebra or college-level calculus, statistics and other related topics.

Design, Web Design/ Development

- HOW Design University — How Design University (How U) offers free and paid online lessons on graphic and interactive design, and has opportunities for those who would like to teach.

- HTML Dog — HTML Dog is specifically focused on Web development tutorials for HTML, CSS and JavaScript coding skills.

- Skillcrush — Skillcrush offers professional web design and development courses aimed at one who is interested in the field, regardless of their background — with short, easy-to-consume modules and a 3-month Career Blueprints to help students focus on their career priorities.

- Hack Design — Hack Design, with the help of several dozen designers around the world, has put together a lesson plan of 50 units (each with one or more articles and/or videos) on design for Web, mobile apps and more by curating multiple valuable sources (blogs, books, games, videos, and tutorials) — all free of charge.

Online Education Resources

General – Children and Adults

- Scratch – Imagine, Program, Share — Scratch from MIT is a causal creative learning site for children, which has projects that range from the solar system to paper planes to music synths and more.

- Udemy — Udemy hosts mostly paid video tutorials in a wide range of general topics including personal development, design, marketing, lifestyle, photography, software, health, music, language, and more.

- E-learning for kids — E-learning for Kids offers elementary school courses for children ages 5-12 that cover curriculum topic including math, science, computer, environment, health, language, life skills and others.

- Ed2go — Ed2go aims their 'affordable' online learning courses at adults, and partners with over 2,100 colleges and universities to offer this virtual but instructor-led training in multiple categories — with options for instructors who would like to participate.

- GCF Learn Free — GCFLearnFree.org is a project of Goodwill Community Foundation and Goodwill Industries, targeting anyone look for modern skills, offering over 1,000 lessons and 125 tutorials available online at anytime, covering technology, computer software, reading, math, work and career and more.

- Stack Exchange — StackExchange is one of several dozen Q+A sites covering multiple topics, including Stack Overflow, which is related to computer technology. Ask a targeted question, get answers from professional and enthusiast peers to improve what you already know about a topic.

- HippoCampus — HippoCampus combines free video collections on 13 middle school through college subjects from NROC Project, STEMbite, Khan Academy, NM State Learning Games Lab and more, with free accounts for teachers.

- Howcast — Howcast hosts casual video tutorials covering general topics on lifestyle, crafts, cooking, entertainment and more.

- Memrise — Lessons on the Memrise (sounds like 'memorize') site include languages and other topics, and are presented on the principle that knowledge can be learned with gamification techniques, which reinforce concepts.

- SchoolTube — SchoolTube is a video sharing platform for K-12 students and their educators, with registered users representing over 50,000 schools and a site offering of over half a million videos.

- Instructables — Instructables is a hybrid learning site, offering free online text and video how-to instructions for mostly physical DIY (do-it-yourself) projects that cover various hands-on crafts, technology, recipes, game play accessories and more. (Costs lie in project materials only.)

- creativeLIVE — CreativeLive has an interesting approach to workshops on creative and lifestyle topics (photography, art, music, design, people skills, entreprenurship, etc.), with live access typically offered free and on-demand access requiring purchase.

- Do It Yourself — Do It Yourself (DIY) focuses on how-tos primarily for home improvement, with the occasional tips on lifestyle and crafts topics.

- Adafruit Learning System — If you're hooked by the Maker movement and want to learn how to make Arduino-based electronic gadgets, check out the free tutorials at Adafruit Learn site — and buy the necessary electronics kits and supplies from the main site.

- Grovo — If you need to learn how to efficiently use a variety of Web applications for work, Grovo has paid (subscription, with free intros) video tutorials on best practices for hundreds of Web sites.

General College and University

- edX — The edX site offers free subject matter from top universities, colleges and schools from around the world, including MIT and Harvard, and many courses are 'verified,' offering a certificate of completion for a nominal minimum fee.

- Cousera — Coursera is a learning site offering courses (free for audit) from over 100 partners — top universities from over 20 countries, as well as non-university partners — with verified certificates as a paid option, plus specializations, which group related courses together in a recommended sequence.

- MIT Open Courseware — MIT OpenCourseWare is the project that started the OCW / Open Education Consortium [http://www.oeconsortium.org], launching in 2002 with the full content of 50 real MIT courses available online, and later including most of the MIT course curriculum — all for free — with hundreds of higher ed institutions joining in with their own OCW course materials later.

- Open Yale Courses — Open Yale Courses (OYC) are free, open access, non-credit introductory courses recorded in Yale College's classroom and available online in a number of digital formats.

- Open Learning Initiative — Carnegie Mellon University's (CMU's) Open Learning Initiative (OLI) is course content (many open and free) intended for both students who want to learn and teachers/ institutions requiring teaching materials.

- Khan Academy — Khan Academy is one of the early online learning sites, offering free learning resources for all ages on many subjects, and free tools for teachers and parents to monitor progress and coach students.

- MIT Video — MITVideo offers over 12,000 talks/ lecture videos in over 100 channels that include math, architecture and planning, arts, chemistry, biological engineering, robotics, humanities and social sciences, physics and more.

- Stanford Online — Stanford Online is a collection of free courses billed as 'for anyone, anywhere, anytime' and which includes a wide array of topics that include human rights, language, writing, economics, statistics, physics, engineering, software, chemistry, and more.

- Harvard Extension School: Open Learning Initiative — Harvard's OLI (Open Learning Initiative) offers a selection of free video courses (taken from the edX selection) for the general public that covers a range of typical college topics, includings, Arts, History, Math, Statistics, Computer Science, and more.

- Canvas Network — Canvas Network offers mostly free online courses source from numerous colleges and universities, with instructor-led video and text content and certificate options for select programs.

- Quantum Physics Made Relatively Simple — Quantum Physics Made Relatively Simple' is, as the name implies, a set of just three lectures (plus intro) very specifically about Quantum Physics, form three presentations given by theoretical physicist Hans Bethe.

- Open UW — Open UW is the umbrella initiative of several free online learning projects from the University of Washington, offered by their UW Online division, and including Coursera, edX and other channels.

- UC San Diego Podcast Lectures — Podcast USCD, from UC San Diego, is a collection of audio and/or video podcasts of multi-subject university course lectures — some freely available, other only accessible by registered students.

- University of the People — University of the People offers tuition-free online courses, with relatively small fees required only for certified degree programs (exam and processing fees).

- NovoEd — NovoEd claims a range of mostly free 'courses from thought leaders and distinguished professors from top universities,' and makes it possible for today's participants to be tomorrow's mentors in future courses.

IT and Software Development

Online Education Degree

- Udacity — Udacity offers courses with paid certification and nanodegrees — with emphasis on skills desired by tech companies in Silicon Valley — mostly based on a monthly subscription, with access to course materials (print, videos) available for free.

- Apple Developer Site — Apple Developer Center may be very specific in topics for lessons, but it's a free source of documentation and tutorials for software developers who want to develop apps for iOS Mobile, Mac OS X desktop, and Safari Web apps.

- Google Code — As with Apple Developer Center, Google Code is topic-narrow but a good source of documentation and tutorials for Android app development.

- Code.org — Code.org is the home of the 'Hour of Code' campaign, which is aimed at teachers and educators as well as students of all ages (4-104) who want to teach or learn, respectively, computer programming and do not know where to start.

- Mozilla Developer Network — MDN (Mozilla Developer Network) offers learning resources — including links to offsite guides — and tutorials for Web development in HTML, CSS and JavaScript — whether you're a beginner or an expert, and even if you're not using Mozilla's Firefox Web browser.

- Learnable — Learnable by Sitepoint offers paid subscription access to an ebook library of content for computers and tablets, and nearly 5,000 videos lessons (and associated code samples) covering software-related topics – with quizzes and certification available.

- Pluralsight — Pluralsight (previously PeepCode) offers paid tech and creative training content (over 3,700 courses and 130K video clips) for individuals, businesses and institutions that covers IT admin, programming, Web development, data visualization — as well as game design, 3D animation, and video editing through a partnership with Digital-Tutors.com, and additional software coding lessons through Codeschool.com.

- CodeHS — CodeSchool offers software coding lessons (by subscription) for individuals who want to learn at home, or for students learning in a high school teacher-led class.

- Aquent Gymnasium — Gymnasium offers a small but thorough set of free Web-related lesson plans for coding, design and user experience, but filters access by assessing the current knowledge of an enrollee and allows those with scores of at least 70% to continue.